Joe Meek was as much a pop producer at heart as any of those, albeit for a shorter period (three UK number ones), yet his pioneering DIY and independently rebellious auteur image has given him the kind of outsider status that cults thrive on. Following the close friends, associates and fans interviewing documentary released to art festival showings earlier this year A Life In The Death Of Joe Meek comes the premiere as part of the London Film Festival on 25th October and again on the 28th of Telstar, the film of the well regarded play co-written, adapted and directed by Nick Moran, starring acclaimed musical actor Con O'Neill as Meek and also featuring Kevin Spacey, Pam Ferris, Ralf Little, James Cordon, Rita Tushingham, Nigel Harman, erm, Carl Barat and Justin Hawkins. High time, then, to look into why he's so revered.

Robert George Meek, born 1929 in Newent, Forest Of Dean (home to the National Birds of Prey Centre and Europe's largest cul-de-sac) had an early interest in putting on a show, staging magic shows for children and being dressed as a girl by his mother. It was a fascination with electrics that was his real first love, though, building his own gadgets by taking the backs of old radios and record players, rigging up nascent PAs and setting up a mobile DJing kit. A National Service spell in the RAF as a radar technician helped his interest along. After demob, he bought an acetate disc cutter and in 1953 moved to London to become a sound engineer for a radio production company that made programming for Radio Luxembourg and then a studio recording engineer, and would surreptitously add effects and tricks onto recordings regardless of whether he'd been asked to. One such ploy saw him mess with the final mix of Humphrey Lyttleton's Bad Penny Blues, putting the piano part to the front and distorting the bass. It became trad jazz's first top 20 single. By day working in studios, he set up a small recording facility in his flat where he'd record tone deaf demos of songs he'd written, mostly inspired by his point of obsession hero Buddy Holly.

After being sacked from Lansdowne Recording Studios (where the Sex Pistols would later record Anarchy In The UK, following any number of 60s British Invaders) due to a clash of personalities with the owner, in 1960 Meek co-founded Triumph Records, possibly the first British independent label. One of its first releases was his own I Hear a New World - An Outer Space Music Fantasy. Playing on Meek's penchant for outer space and equipment manipulation and largely made flesh by The Blue Men, an adapted skiffle group, it was Meek's largely instrumental attempt "to create a picture in music of what could be up there in outer space", a blend of the band, found sounds, electronic pulses and special effects that was less late 50s kitsch the subject might suggest than presaging psychedelia and Eno ambient. Due to finance issues only the first side came out as an EP, the whole album not fully issued until 1991 (the 2002 reissue has a half hour interview with Meek about his processes added).

Joe Meek/The Blue Men - I Hear A New World

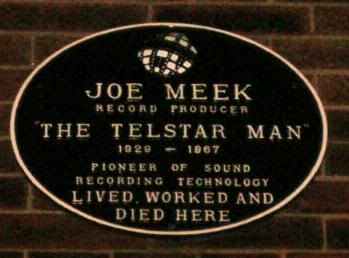

There were more conventional releases, most notably teenage fantasy Angela Jones by Michael Cox, heavily supported by Jack Good's television programmes and making number seven, arguably not going higher due to Triumph's inability to press enough copies through independent pressing plants. The label proved to be somewhat short of cost effective, but a rich toy emporter benefactor stepped in and enabled Meek to set up RGM Sound Ltd and upgrade both studio and flat to a premises above a leather goods shop on 304 Holloway Road, N7.

Photo adapted for size from Houseplant Picture Studio, which also reveals the leather goods shop is now a cycle store

Holloway Road wasn't the most comfortable of settings, being on the third floor, but Meek knew he now had the room and wherewithal to do what he pleased with the sounds he was trying to create. He knew he couldn't create them without a sideman, though, and through publisher auditions met Geoff Goddard, a Royal Academy of Music trained pianist whom Meek briefly attempted to launch as Anton Hollywood. It was as a writer he'd become more successful, not least when the first release from the new studios became a number one. John Leyton was a rising young actor (in fact he briefly appears in Telstar) who like many a successful with teenagers actor of the day was hastened towards the studio, and after a couple of flops Goddard offered the orchestral death disc Johnny Remember Me, which he would claim had been written with the aid of a seance. The recording session itself leant itself to many a Meek legend, with vocals recorded in the bathroom and a string section arranged on the stairs for the acoustics necessary to create the eerie, echoey sound Meek had made his own, plus the then in-house backing band The Outlaws, including future Dave cohort Chas Hodges. At the time Leyton was appearing in ITV department store drama Harpers West One as a character called Johnny St. Cyr and his manager arranged for the song to be mock-performed on the show, with the required chart results.

John Leyton - Johnny Remember Me

Nobody had heard a hit quite like this before, especially not one that clocked up five weeks atop the chart, and Meek's setup became an industry talking point, as much anti ("a recording studio is the place to record" one columnist railed) as pro, Meek claiming "I make records to entertain the public, not square connoisseurs who just don’t know”. A lot of his recordings weren't hits at all, but most were deeply fascinating. Overseen by a pair of men deeply fascinated by the occult and taken to visiting graveyards and haunting sites overnight, Screaming Lord Sutch, whose stage antics essentially invented Alice Cooper, recorded and plotted outlandish publicity stunts with Joe, and The Moontrekkers' Night Of The Vampire was banned by the BBC and has been credited with inventing goth about two decades too early (the band hadn't been instrumental until Meek worked with them, although the singer's sacking is something we doubt Rod Stewart has had much cause to bemoan lately). Some of these recordings were known to have been rejected by labels and mastertape cutting engineers as they would damage domestic speakers.

The Moontrekkers - Night Of The Vampire

For a good period of this time Meek had his next big success under his nose but hadn't realised it until his latest in-house band were asked to back Billy Fury on tour. The Tornados - Alan Caddy on lead guitar, Heinz Burt on bass, Matt Bellamy of Muse's father George on rhythm guitar, Roger Lavern on keyboards and drummer Clem Cattini (who went on to hold the record for most UK number ones played on, appearing on 44 chart toppers ranging from It's Not Unusual, The Sun Ain't Gonna Shine Anymore and You Don't Have to Say You Love Me to Grandad, Two Little Boys and Ernie The Fastest Milkman In The West) - were the guinea pigs for Meek's tribute to the AT&T communications satellite Telstar, which went into orbit in July 1962, five weeks before the single named after it was released. Making heavy use of Goddard's clavioline keyboard and inspired by I Hear A New World's advances, it not only topped the UK chart for five weeks but the Billboard Hot 100 for three, making the Tornados the first UK band to have a US number one, estimated worldwide sales standing at five million. Famously, it was also one of Margaret Thatcher's Desert Island Discs. The band did have other hits, Globetrotter reaching number five and Robot nineteen, but Meek was by this time high on the hog and buying ever more equipment for the studio, at least until French composer, Jean Ledrut accused Meek of plagiarism, claiming that the tune of Telstar had been copied from his own earlier work Le Marche d'Austerlitz. It is now thought very unlikely that Meek would have been aware of Ledrut, but the resultant lawsuit prevented him from receiving any further royalties until 1968, by which time it was too late.

The Tornados - Telstar

The Tornados' German bass player, Heinz Burt, wasn't allowed to merely drift away, however. Homosexual Meek - a lot of his depression and paranoia has been attributed to his feelings over his sexual proclivities, not legalised in the UK until 1967 - had taken an unconsummated shine to Burt, and when Goddard came up with Eddie Cochran tribute Just Like Eddie Meek, who had already split Burt from both band and professional surname, persuaded him to record it with yet another Meek band, The Saints, plus Outlaws guitarist Ritchie Blackmore (later of Deep Purple and Rainbow). A number five in August 1963, Meek was now in position where he could independently record a string of unknowns and sell the results to the major labels for big money, meaning the Meek rarities market is almost as crowded as the Northern Soul catalogue.

On November 11th 1963 Meek, who was as openly homosexual as the times would allow, was arrested for "importuning for immoral purposes" in a gents near the studio and fined £15, a possible set up and certainly one that would lead to incidents of blackmail which didn't help his mental state or legendary fits of temper. Additionally the beat group era who were more reliant on self-written songs and the pure pop of melody rather than svengali producers was on his tail with the rise of the Beatles and Merseybeat, although one such group, The Honeycombs, came under Meek's auspices. Famed at the time for having a female drummer, one Honey Lantree who supposedly inspired Karen Carpenter to take up the drums, they provided him with his last UK number one, the stomping Have I The Right featuring a bass drum sound achieved by the group stamping on the stairs of the studio, the underside of which had been attached four microphones.

However, the success came at a personal price - Geoff Goddard launched legal proceedings claiming that the prolific Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley had plagirised his own Give Me The Chance, and not only lost but saw Meek side against him. Goddard left Holloway Road employment and faded out of the business, taking a job in catering at Reading University where he ended up working in the kitchens (his later colleagues included two hard-up students who became Yan and Noble of British Sea Power, who would write The Lonely about him) and died in May 2000.

Meek's professional life was coming apart at the seams. Tom Jones, who he'd auditioned and turned down, was having hits. The Tornados and Heinz were fading away while the Honeycombs fell apart within two years. The deals Meek signed with major labels were full of loopholes and financing wasn't there. Meek was heavily into pills, including LSD, and seances, an unwise combination. Some of his music was as inventive as ever, moving on to psychedelia, Mod and freakbeat...

The Syndicats - Crawdaddy Simone

Glenda Collins - It's Hard To Believe It

...and after Merseybeat band The Cryin' Shames took a Meek produced cover of The Drifters' Please Stay to the top thirty in 1966 Brian Epstein supposedly offered his more famous charges to Meek with no dice, and when a London visiting Phil Spector called to express his love of the sound an increasingly paranoid Meek, who already believed Decca were bugging the premises, angrily accused Spector of stealing his ideas before hanging up. Meek ended up placing listening devices around the studio in case musicians were talking about him. At one point he was found beaten up and unconscious in his car, perhaps related to gangland threats against the Tornados as much as those around his sexuality.

When in January 1967 police found the body of Bernard Oliver, an alleged rent boy and past associate, mutilated and disposed of in a suitcase, Meek was alarmed when reports sugested police would be interviewing all known homosexuals in the city. On 3rd February 1967, the eighth anniversary of his hero Buddy Holly's death, heavily in debt and drug-paranoid, Meek was attempting to record his latest studio assistant when landlady Violet Shenton was called up, Meek believed to have been on the verge of being thrown out for non-payment of rent. Meek had a single barreled shotgun, registered to Heinz Burt and confiscated by Meek some time before when Burt left after a brief period living in the property. He now retrieved it and used it to blast Shenton in the back of the head, before turning it on himself. He was subsequently buried at Newent Cemetery.

Meek's legacy took some time to reassert itself, largely through the work of collectors and obscurists from the late 70s onwards. A 1991 BBC2 Arena documentary, The Strange Story Of Joe Meek (which we've found on torrent sites if you're interested) is credited with kickstarting the renaissance as well as a reissue and excavation program which continues. His influence is felt across music, from pop producers to leftfield beatmakers, both Orbital and Saint Etienne regarding him as a major inspiration. He pioneered effects in overdubbing, tape manipulation, miking, distortion, compression, reverb, instrument seperation, recording of rhythm sections, composite recording and sampling found sounds, always taking the sound spectrum first ahead of the tune, single-mindedly searching for a unique sonic signature for each record, these out of the way, supposedly unworkable advances now treated as standard. Unlike his contemporary Phil Spector, he wouldn't hire great numbers of musicians and backing singers to create the overwhelming effect but would record individually and mix together as he wanted. Meek turns up as a character in acclaimed gangland novel The Long Firm - writer Jake Arnott has a cameo role in the film - and songs have been written in his honour by the likes of Wreckless Eric, Graham Parker and, if you believe her story of the background to her single A Change Would Do You Good, Sheryl Crow. Meek may not be the most famous name outside certain circles, but his working methods were as groundbreaking as his life was fraught.

Further reading:

The Joe Meek Appreciation Society, formed in 1991, is "dedicated to keeping Joe Meek's name and his musical legacy alive" and runs a full membership scheme as well as keeping track on all current movements. This, oddly, is not to be confused with Joe Meek RGMAS. Meanwhile the dual language The Joe Meek Page attempts an entire discography. There's a few newspaper and magazine pieces we've trawled to write the above, but Jon Savage's essay for Observer Music Monthly on Meek's homosexuality, with reference to celebrated Tornados B-side Do You Come Here Often?, adds extra background for the times.

BUYER'S GUIDE: As stated somewhere in there, new discoveries are turning up all the time, the so-called "Tea Chest demos" as all his tapes were kept in 67 tea chests still being excavated - 1850 such tapes recently failed to sell at general auction despite including in the haul early recordings of Tom Jones, Gene Vincent and Billy Fury, plus David Bowie's first band The Konrads. Joe Meek: The RGM Legacy - Portrait of a Genius is a four disc box set that attempts a whole career overview, including rarities, demos, interview clips and alternate versions, plus liner notes by Bob Stanley. Telstar - The Hits Of Joe Meek reduces the 'hits' to two discs and 36 tracks on Sanctuary's budget promotion, while It's Hard To Believe It - The Amazing World Of Joe Meek is a more judiciously cherrypicked 21 track compilation. 56 track Joe Meek: The Alchemist of Pop fits somewhere in the middle. The EP Collection recreates twelve four-track EPs, including Telstar. I Hear A New World is reissued every so often. Let's Go - Joe Meek's Girls shows he could work really well with female singers, including the Sharades, the trio we singled out in the girl group Primer, while Joe Meek Freak Beat: You're Holding Me Down demonstrates that as the 60s wore on he didn't lose all his rampaging touch.

No comments:

Post a Comment